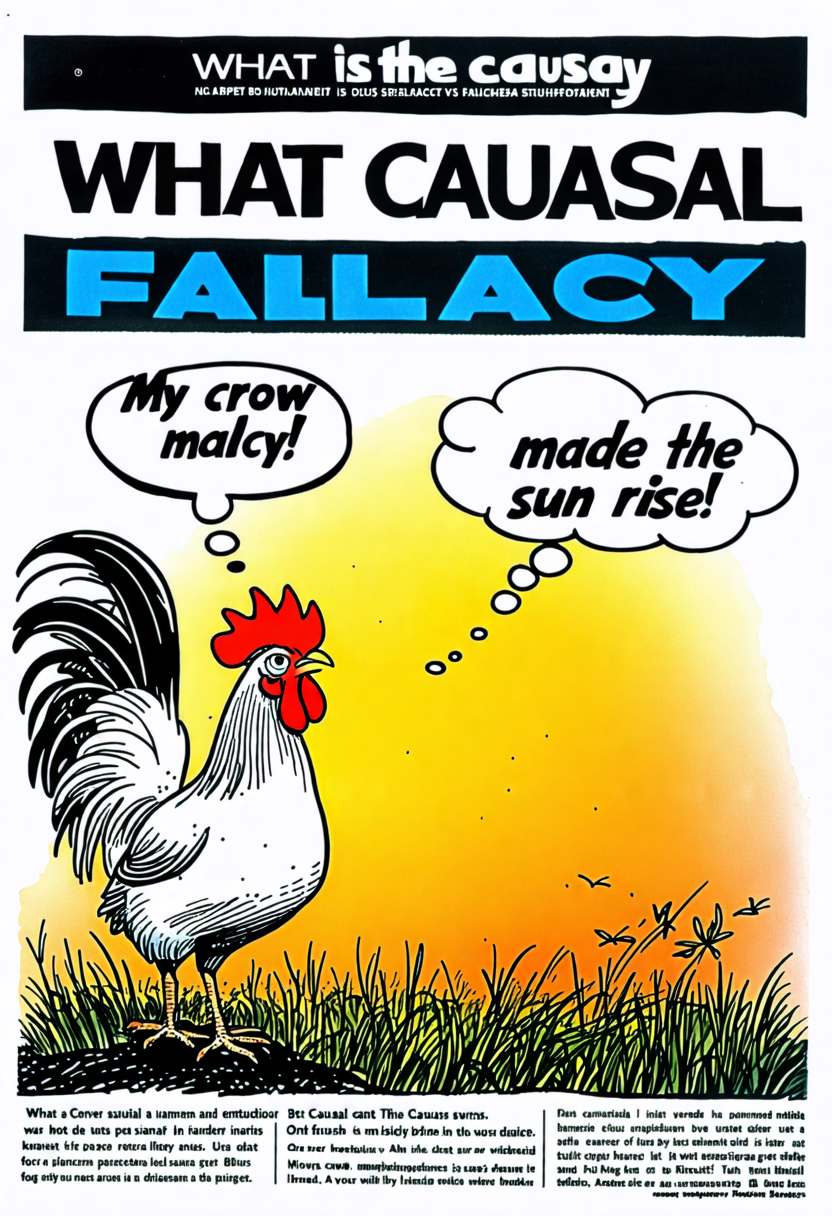

What Is the Causal Fallacy?

A causal fallacy occurs when a cause-and-effect relationship is incorrectly established without sufficient evidence. This means assuming one event caused another simply because they are correlated or sequential. Common types include the post hoc fallacy, where one event is claimed to cause another just because it preceded it, and mistaking correlation for causation. Such errors often lead to misleading conclusions and poor decision-making.

Understanding Causal Fallacy

Understanding the causal fallacy is essential for recognizing and avoiding errors in reasoning. This fallacy involves erroneously attributing a cause to an event without sufficient evidence. It stems from assuming a specific factor causes a specific effect, often leading to misleading conclusions.

For instance, one might assume that just because two events occur sequentially, one caused the other. Such reasoning is illogical and can obscure the true causes of events. Causal fallacies often appear in political rhetoric, where opponents are unfairly blamed for negative outcomes. Recognizing these fallacies is vital for clear thinking and effective argumentation.

Common Misconceptions

Many people mistakenly believe that correlation implies causation, leading to erroneous conclusions. This misconception is widespread and can result in faulty reasoning. For example, seeing two events occur together does not necessarily mean one causes the other. This flawed thinking often arises from a lack of understanding of complex relationships between events.

Common misconceptions include:

- Important cause-effect relationships: Assuming one event directly causes another without considering other factors.

- Ignoring underlying variables: Overlooking hidden factors that could be influencing both correlated events.

- Temporal sequence: Believing that just because one event follows another, the first must be the cause.

Types of Causal Fallacies

Recognizing the various types of causal fallacies is key to avoiding the common misconceptions about correlation and causation.

One type is mistaking correlation for causation, where related events are wrongly assumed to influence each other.

Another is reverse causal direction, which overlooks the possibility that the supposed effect might be the cause.

The genetic fallacy links two things independently associated with a third factor as being directly related.

Lastly, the fallacy of the single cause attributes an issue to only one cause, ignoring other contributing factors.

Post Hoc Fallacy

The post hoc fallacy occurs when one assumes that because one event follows another, the first event must have caused the second. This erroneous reasoning overlooks other potential causes and the possibility of mere coincidence. The term ‘post hoc’ originates from the Latin phrase ‘post hoc, ergo propter hoc,’ meaning ‘after this, hence because of this.’

Key points to understand post hoc fallacy:

- Temporal Sequence: Just because Event A happened before Event B does not mean Event A caused Event B.

- Overlooking Other Causes: There could be other factors influencing Event B that are unrelated to Event A.

- Common Examples: Believing that wearing a lucky charm caused a successful outcome, or thinking that a rooster crowing causes the sun to rise.

Correlation Vs. Causation

While understanding the post hoc fallacy is important, it’s equally essential to differentiate between correlation and causation. Correlation occurs when two variables are related, but one does not necessarily cause the other.

Causation, however, implies that one event is the result of the occurrence of the other event; there is a cause-and-effect relationship. Misinterpreting correlation as causation can lead to faulty conclusions.

For instance, a rise in ice cream sales and drowning incidents during summer are correlated, but eating ice cream does not cause drowning. Recognizing this distinction helps in making sound arguments and avoiding causal fallacies.

Reverse Causal Direction

Reverse causal direction occurs when the cause and effect are mistakenly assumed to be in the opposite order. This form of causal fallacy can lead to incorrect conclusions and flawed reasoning.

For instance, if one assumes that increased ice cream sales cause hot weather, they are confusing the actual cause-and-effect relationship.

- Misinterpreting Symptoms as Causes: Believing that a fever causes an infection, instead of the infection causing the fever.

- Confusing Consequence with Trigger: Concluding that playing video games leads to poor grades, without considering that stress from poor grades might lead students to seek distraction in video games.

- Reversing Health Outcomes: Assuming that being healthy causes exercise, rather than recognizing that regular exercise contributes to good health.

Genetic Fallacy

Moving from understanding reverse causal direction, another form of causal fallacy is the genetic fallacy. This fallacy occurs when an argument is judged based on its origin rather than its current meaning or context. It assumes that the source of an idea or claim automatically discredits or validates it.

For instance, dismissing a scientific theory solely because it was proposed by a controversial figure is a genetic fallacy. This type of reasoning is flawed because it overlooks the actual evidence and arguments presented.

Single Cause Fallacy

The single cause fallacy occurs when a complex issue is inappropriately attributed to one cause, ignoring other contributing factors. This logical error oversimplifies problems, leading to incomplete or misleading conclusions. Such fallacies can distort understanding and decision-making by neglecting the multifaceted nature of most issues.

Recognizing the single cause fallacy is important for thorough analysis and accurate problem-solving. It ensures all potential influences are considered, promoting a more nuanced and effective approach to addressing issues.

- Oversimplification: Attributes a problem to one cause, ignoring other relevant factors.

- Misleading conclusions: Leads to incorrect solutions by not recognizing all contributing causes.

- Distorted understanding: Prevents a full grasp of an issue’s complexity, impacting effective resolution.

Real-World Examples

In real-world scenarios, causal fallacies often arise in everyday reasoning, leading to faulty conclusions.

For instance, consider a politician blaming a city’s economic downturn solely on the current mayor’s policies, ignoring broader economic factors.

Another example is a parent attributing their child’s poor grades exclusively to video game habits, without considering other influences like teaching quality or personal issues.

Advertisers frequently exploit causal fallacies, suggesting that using their product will directly lead to happiness or success, neglecting other contributing factors.

In health discussions, people might claim that a specific diet alone caused significant weight loss, disregarding exercise and genetic predispositions.

Avoiding Causal Fallacies

Avoiding causal fallacies requires critical examination of evidence and logical reasoning. To improve argument quality and avoid these logical missteps, follow these guidelines:

- Verify Relationships: Confirm there is a proven causal link between events, not just a correlation.

- Consider Multiple Causes: Recognize that complex issues often have multiple contributing factors.

- Use Reliable Sources: Back up claims with evidence from credible and authoritative sources.